The Happenings of the Parliament

The Closing Ceremony

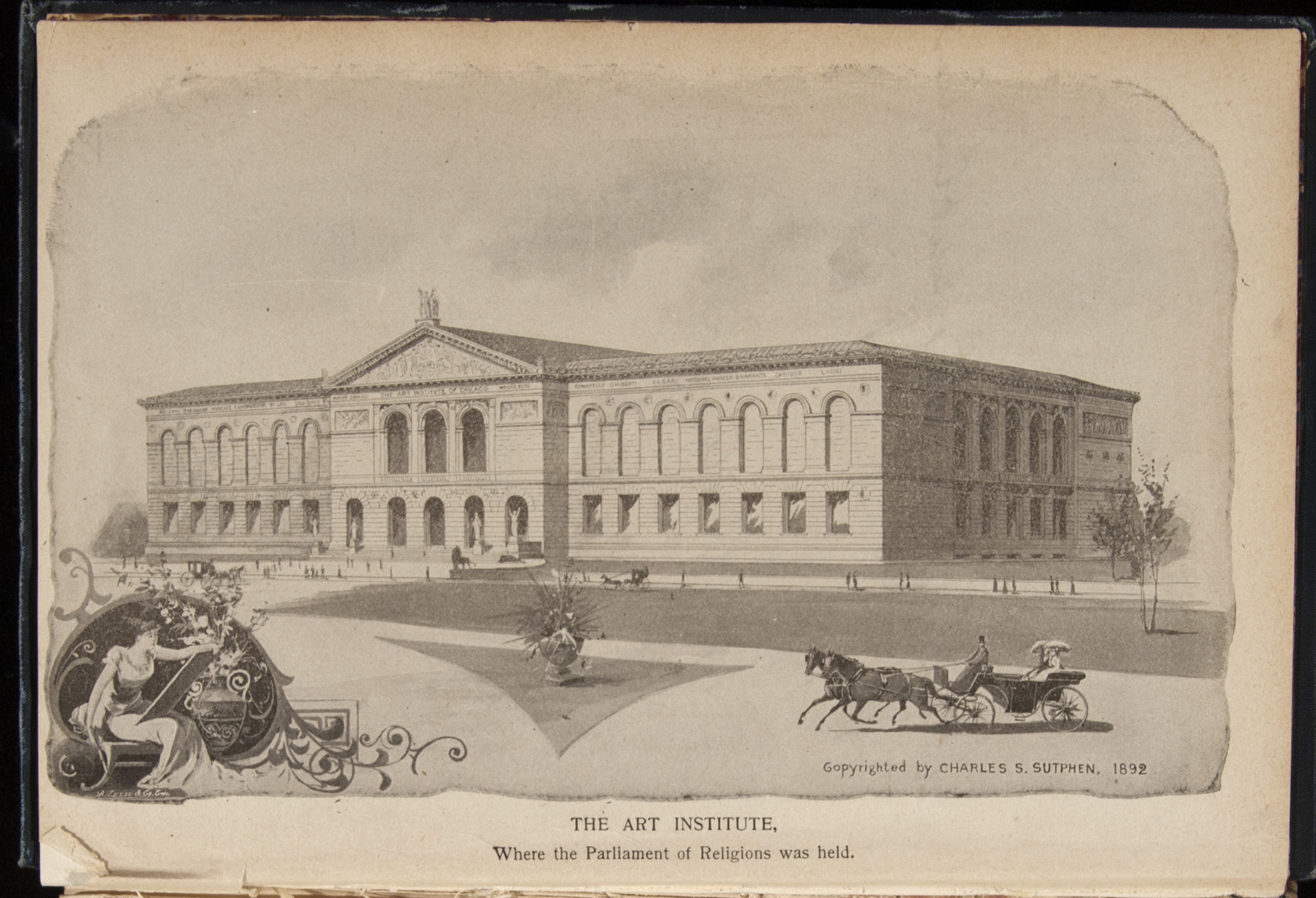

After sixteen continuous days of religious exchange, the Parliament drew to a close on September 27. Some seven thousand people attended the final festivities—nearly double the audience of the opening ceremonies just sixteen short days earlier. So many people were in attendance that the closing remarks had to be repeated a second time to an overflow audience seated in Washington Hall adjacent to the Hall of Columbus. Once again, the representatives sat underneath the flags of their respective nations, the room brilliantly lit under a myriad of lights. The enthusiasm of the room was only matched by an utter somberness at the thought of the conclusion of this historic assembly.

Concluding remarks were given by many of the Asian delegates that had certainly left an indelible mark on not only the Parliament, but also on the American audiences they had spoken before. As so appropriately put by Mr. Mozoomdar of the Brahmo-Somaj, “For once in history all Religions have made their peace, all nations have called each other brothers, and their representatives have for seventeen days stood up morning after morning to pray Our Father, the universal Father of all, in Heaven.” Although the Parliament had initially been conceived by Christian leaders as a platform to distinguish the Gospel from all other “lower” religions, it instead became a promise of greater equality in the eyes of the Asian delegates. Despite some uncourteous moments shown to specific Asian representatives, the Parliament had proven to be a forum of generally open, brotherly exchange of ideas and philosophies.

Perhaps even more important, the Parliament promised specific developments for different peoples. For example, in his closing speech, Mr. Hirai of the Japanese Buddhist delegation believed that the Parliament signified a “step towards the ideal goal […] the realization of international justice.” This would have been a reference to the unequal treaties that the United States imposed on Japan in 1858 that, to an extent, undermined Japanese sovereignty. Several delegates from the Japanese cohort made explicit reference to these treaties in their speeches they presented throughout the course of the Parliament. Similarly, the Honorable Pung Kwang Yu made reference to the unequal treatment of Chinese people living in the United States in his closing remarks. He wrote, “I have a favor to ask of all the religious people of America, and that is that they will treat, hereafter, all my countrymen just as they have treated me”. As First Secretary of the Chinese Legation in Washington D.C., his obligations rested in assuring the fair treatment of his people, and he clearly uses the prominence of the Parliament as a way to fulfill his obligations. For some, such as Anagarika Dharmapala, their goal for the Parliament was simply to bring their religious traditions to the attention of a Western audience. The opening statement in his concluding remarks reads, “This Congress of Religions has achieved a stupendous work in bringing before you the representatives of the religions and philosophies of the East.” And for others, like Swami Vivekananda, in addition to the Parliament being a stage for which to speak on the religious doctrines of Hinduism, it was also an opportunity to promote unity. He writes, “Much has been said of the common ground of religious unity… If anyone here hopes that his unity will come by the triumph of one of these religions and the destruction of the others, to him I say: “Brother, yours is an impossible hope.”

Finally, the Parliament concluded with the triumphant singing of the Hallelujah chorus. The delegates would return to their respective lands and continue their work. A September 29th article from the Chicago Daily Tribune comments on the success of the Parliament. First, it remarks on how successful the entire endeavor has been in documenting the dogmas and quintessential statements of the various religious sects, and that in doing so, “The contributions to religious literature have been of the utmost value”. More universally, it reads that, “It has been found that at the bottom of all religions there are the ideas of the brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God”, so despite the prospect of a universal religion not at all likely, although it was considered a possible outcome of the Parliament in the beginning, religious work can now be carried out, “with more facility and success because of extended acquaintance, a larger degree of toleration, and the probable absence of antagonisms growing out of ignorance and prejudice.” All in all, this tremendous occasion brought the people of the world together, for however brief a period, and shed light on the possibility of a brotherly unity of mankind regardless of nationality, ethnicity, and especially religious identity.