- Top

- Paris Exposition

- Movement Goes Global

- Fuler & Yacco

Room No. 2

The Asian Spin at the World’s Fairs

Â

Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies, 2008.

Source: McNay Art Musuem

Title

The idea for a World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893 came from the Hon. Charles Carroll Bonney (1831-1903), a well-known and successful judge on the Supreme Court of Illinois (Fig. 1). As an active member of the New Jerusalem Church (also known as Swedenborgian), Bonney had a deep conviction about the harmony of religions. He saw the World’s Parliament as “an epoch-making event in the history of human progress, marking the dawn of a new era of brotherhood and peace.”[1]Bonney’s vision reflected the vision of Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition as an exalted celebration of human progress, but it gave it a distinctly religious focus. Bonney hoped that the Parliament would not only bring religious leaders together in an expression of mutual sympathy, but would “unite all religion against all irreligion” (Bonney 1895: 325). This had particular significance for Bonney and other religious leaders who felt both confident and overshadowed by the extraordinary technological prowess that characterized other aspects of the Exposition. To say, as some did, that “Religion is the greatest fact of History,”[2]was not something that one could merely assume. Bonney and others hoped that the Parliament would be a visible demonstration of the importance of religion as a global force amidst the instability of late nineteenth-century modernity.

[1] Charles C. Bonney, “The World’s Parliament of Religions,” The Monist 5 (1895): 322.

[2] John Henry Barrows, The World’s Parliament of Religions. 2 vols. (Chicago: The Parliament Publishing Company, 1893), Vol. 1: vii.

Room No. 2

The Asian Spin at the World’s Fairs

Â

Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies, 2008.

Source: McNay Art Musuem

Title

The idea for a World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893 came from the Hon. Charles Carroll Bonney (1831-1903), a well-known and successful judge on the Supreme Court of Illinois (Fig. 1). As an active member of the New Jerusalem Church (also known as Swedenborgian), Bonney had a deep conviction about the harmony of religions. He saw the World’s Parliament as “an epoch-making event in the history of human progress, marking the dawn of a new era of brotherhood and peace.”[1]Bonney’s vision reflected the vision of Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition as an exalted celebration of human progress, but it gave it a distinctly religious focus. Bonney hoped that the Parliament would not only bring religious leaders together in an expression of mutual sympathy, but would “unite all religion against all irreligion” (Bonney 1895: 325). This had particular significance for Bonney and other religious leaders who felt both confident and overshadowed by the extraordinary technological prowess that characterized other aspects of the Exposition. To say, as some did, that “Religion is the greatest fact of History,”[2]was not something that one could merely assume. Bonney and others hoped that the Parliament would be a visible demonstration of the importance of religion as a global force amidst the instability of late nineteenth-century modernity.

[1] Charles C. Bonney, “The World’s Parliament of Religions,” The Monist 5 (1895): 322.

[2] John Henry Barrows, The World’s Parliament of Religions. 2 vols. (Chicago: The Parliament Publishing Company, 1893), Vol. 1: vii.

Religion: Room 1 Sub-room 1

- Top

- Paris Exposition

- Movement Goes Global

- Fuler & Yacco

[dot-end][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" bg_image="2017" bg_position="left top" bg_repeat="no-repeat" bg_color="#3b414f" scene_position="center" layer_one_image="631" text_color="light" text_align="left" id="image-2-top" row_name="Top of Page" color_overlay="#303030" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="fade-in" shape_type=""][vc_column centered_text="true" column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text css_animation="fadeInDown" css=".vc_custom_1563915531583{margin-bottom: 10% !important;}"]Room No. 2[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text css_animation="fadeInDown"]The Asian Spin at the World’s Fairs

Â[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text el_class="bottom-credit"]Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies, 2008.

Source: McNay Art Musuem[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner equal_height="yes" column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]

Title

The idea for a World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893 came from the Hon. Charles Carroll Bonney (1831-1903), a well-known and successful judge on the Supreme Court of Illinois (Fig. 1). As an active member of the New Jerusalem Church (also known as Swedenborgian), Bonney had a deep conviction about the harmony of religions. He saw the World’s Parliament as “an epoch-making event in the history of human progress, marking the dawn of a new era of brotherhood and peace.”[1]Bonney’s vision reflected the vision of Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition as an exalted celebration of human progress, but it gave it a distinctly religious focus. Bonney hoped that the Parliament would not only bring religious leaders together in an expression of mutual sympathy, but would “unite all religion against all irreligion” (Bonney 1895: 325). This had particular significance for Bonney and other religious leaders who felt both confident and overshadowed by the extraordinary technological prowess that characterized other aspects of the Exposition. To say, as some did, that “Religion is the greatest fact of History,”[2]was not something that one could merely assume. Bonney and others hoped that the Parliament would be a visible demonstration of the importance of religion as a global force amidst the instability of late nineteenth-century modernity.

[1] Charles C. Bonney, “The World’s Parliament of Religions,” The Monist 5 (1895): 322.

[2] John Henry Barrows, The World’s Parliament of Religions. 2 vols. (Chicago: The Parliament Publishing Company, 1893), Vol. 1: vii.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text][vid-box name="videoplayback" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/videoplayback.mp4" thumb="3467"/][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][vid-box name="05994" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/05994.mp4" thumb="3469"/][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][vid-box name="0405" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/0405.mp4" thumb="3471"/][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text][vid-box name="coochee" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/coochee.mp4" thumb="3474"/][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][vid-box name="1821" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/1821.mp4" thumb="3470"/][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][vid-box name="4035" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/4035.mp4" thumb="3479"/][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" bg_color="#d1d1d1" scene_position="center" layer_one_image="823" layer_two_image="824" text_color="dark" text_align="left" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none" enable_animation="true" animation="fade-in-from-left"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="image_grid" images="2052" display_title_caption="true" layout="constrained_fullwidth" masonry_style="true" bypass_image_cropping="true" item_spacing="5px" gallery_style="4" load_in_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1563976396921{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text][vid-box name="LoieFullerPicasso" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/LoieFullerPicasso_sd.mp4" thumb="3478"/]

A clip of Loïe Fuller from the documentary, Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies, 2008. Speaker: Tom Gunning, Film Historian.

[button color="see-through-2" hover_text_color_override="#fff" size="small" url="https://youtu.be/ma_vQvPeSiE" text="See the Full Documentary" color_override="#333333"][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]Motion: The Spirit of the Time

The spin of the Asian dance corresponded to the spirit of the time in Europe which, with the development of steam engine, celebrated speed and motion. The emphasis on dance interacted with an important philosophical shift at the time that again quickly gained a global following. "Movement" was discovered as the true characteristic of modern life, especially that of modern urban life, with its moving vehicles, motion pictures, gas and later electric lights that extended the day into night for work and leisure. It was claimed that these urban dynamics actually reflected the workings underlying the universe.

Henri Bergson (1849 - 1941) theory that the élan vital (= vital energy) was the key characteristic of human life and the driving force of all organisms quickly spread in Europe, Asia, and the Americas.[cite note="footnote"][1][/cite]In 1905, Albert Einstein (1879 - 1955) defined matter in motion as but a form of energy with his famous formula E= mc^2. Years later, the American dancer Loïe Fuller, who also was a member of the French Astronomical Society, tried to organize a discussion between Bergson and Einstein to forge a common ground between biology and physics! "Movement" became the name of honor for collective social engagement, for revolution, and even war. It was celebrated on stage, canvas, in sculpture, in architecture and a magical new invention, the motion picture, was able to record movement and make it visible. No wonder that the Lumière Brothers in France and Thomas Edison in the United States chose to record these fast moving dances to highlight their new invention at market fairs all over the world. Movement was the spirit of modernity. Dance was the ideal carrier of this new spirit.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]Dancing Matter into Motion: Loïe Fuller

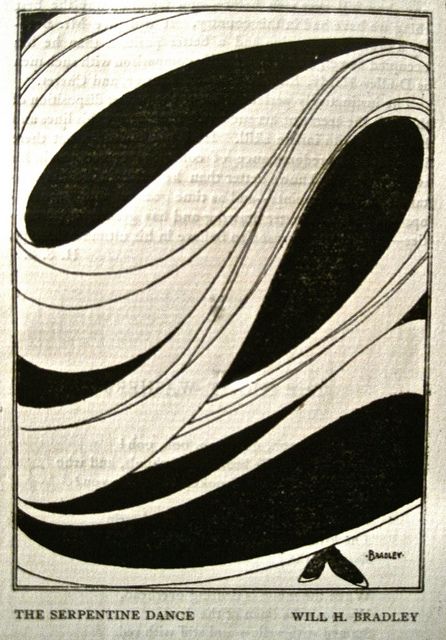

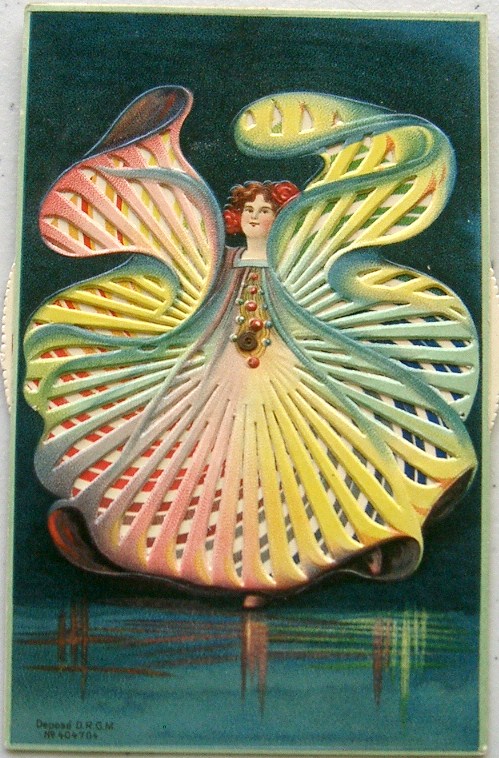

The dancer who embodied the new spirit of motion and movement in Paris, the period's "capital of letters", was the American Loïe Fuller, at the time "the most famous dancer in the world.â€[cite note="footnote"][2][/cite] Her experimental spinning dances with stunning light effects and long silk bands were able to create magical illusions and beauty, of matter dissolving into energy. Her spin dancing and her usage of silk sashes show the effects of her encounters with Asian dance.

She rose to fame in Paris in 1892 and the city remained her home until her death in 1928. In the history of modern aesthetics, Fuller's Paris performances during the 1890s such as the Serpentine Dance and the Fire Dance were an inspiration to artists, photographers, and sculptors of artistic trends as different as Art Nouveau and Futurism. Henri Toulouse-Lautrec drew posters for her, Rodin was her friend, and she thought of using radioactive materials discovered by Madame Curie and her husband for light effects. Eventually, her performances were to leave their mark in Asia to which she owed so much.[cite note="footnote"][3][/cite][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="nectarslider_style" images="2095,2071,2088,2060,2079" flexible_slider_height="true" bullet_navigation_style="see_through" onclick="link_image" css=".vc_custom_1569012859567{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" enable_bg_scale="true" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="nectarslider_style" images="2075,2081,2059,2061" flexible_slider_height="true" bullet_navigation_style="see_through" onclick="link_image" css=".vc_custom_1569012868507{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" bg_color="#d1d1d1" scene_position="center" layer_one_image="823" layer_two_image="824" text_color="dark" text_align="left" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none" enable_animation="true" animation="fade-in-from-left"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" enable_bg_scale="true" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/2" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="image_grid" images="1852,2056" display_title_caption="true" layout="2" masonry_style="true" bypass_image_cropping="true" item_spacing="5px" gallery_style="4" load_in_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1563988068290{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/2" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]When West Meets East

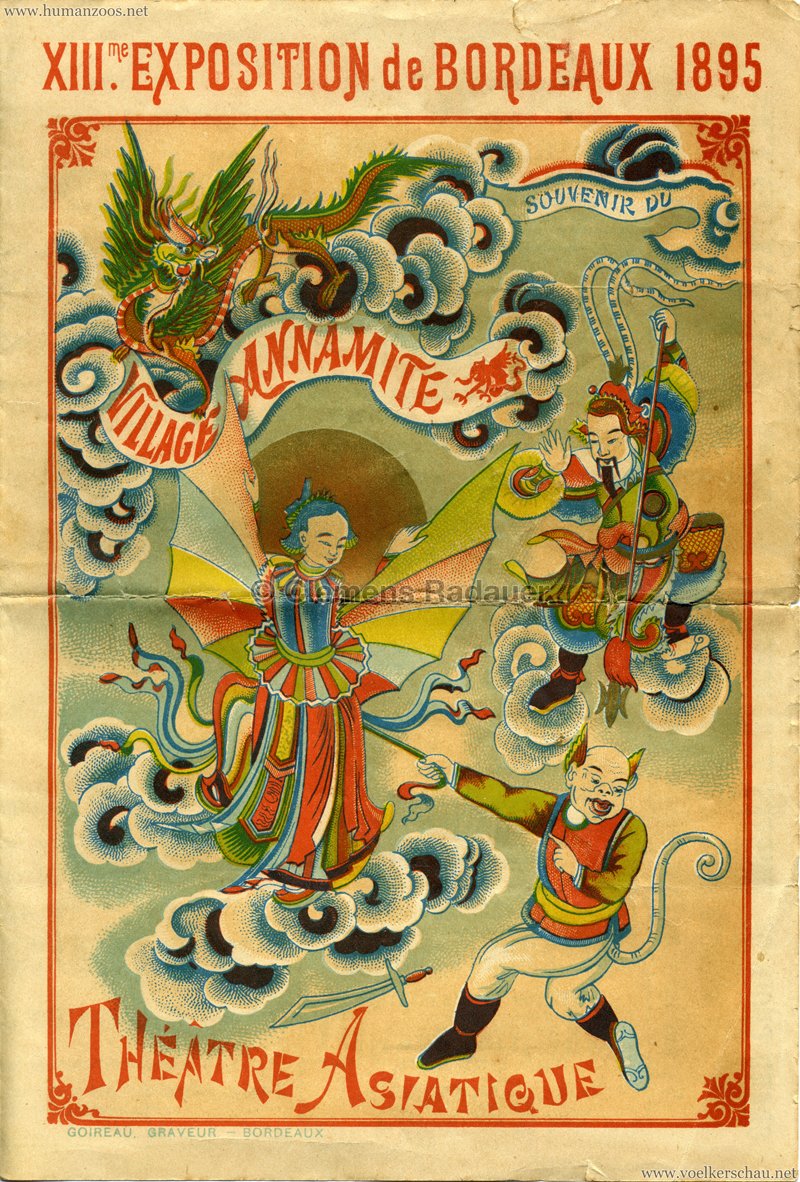

While concepts of “movement†as the spirit of modern times quickly spread to Asia especially to the countries engaging in political and social reform like Japan and China, dance movements in the sense of dance forms also migrated to the west from Asian cultures through the world fairs. Dancers like Loïe Fuller are a prime example of the fruitfulness of these cultural encounters. Asian dance became an inspiration for modern dancers, it stimulated their imagination of modernity. Fuller’s famous sash dance with its swinging motions is an example. It might have been inspired by East Asian dancers performing at the world fairs. In the 1895 poster (on the right) we see a Vietnamese-Chinese dancer dancing with colored sashes with movements indicating swinging and turning. Such a silent migration of forms, gestures, and accoutrements is a common and often overlooked feature in cultural exchanges.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="2/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]The Migration of Form

Dance forms migrate but this never is a question of simply copying. As they are seen and appreciated by dancers from other cultures, they act as inspiration to develop something new. The result will look quite different, but a careful study will reveal the traces of this inspiration.

The films that captured the dance movements of the three Japanese dancers (top, 1894) and of Loïe Fuller (bottom, 1900) both emphasize motion and the celebration of it. The motion of the silk sash in both dances give the dance its outer structure. In both dances, moreover, movements tend to be abstract instead of narrative. The Japanese dance resemble the very popular East Asia ribbon dance with silk being thrown into the air by the dancer. While Fuller’s dance steps suggest that they are indebted to tradition, her movement becomes abstract in form as the body of the dancer disappears in the motion of the silk cloth, leaving a moving image entirely formed by the whirling shape of the silk. The floral patterns in Fuller’s silk dance, furthermore, recalled the Japanese lily which was a dominant motif in the Art Nouveau movement. Fuller’s silk sash dance can be considered the emblem of “Art Nouveau style†of dance, and Art Nouveau sculptors, graphic artists, photographers, and porcelain decorators left and endless array of works depicting this dance of hers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text][vid-box name="4031" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/4031.mp4" thumb="3479"/][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][vid-box name="serpentina" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/serpentina.mp4" thumb="3480"/][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" bg_image="1784" bg_position="left top" bg_repeat="no-repeat" bg_color="#303030" scene_position="center" mouse_sensitivity="20" text_color="light" text_align="left" id="exposition-universelle-paris" row_name="Exposition Universelle Paris" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner background_image="2089" enable_bg_scale="true" column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color="rgba(48,48,48,0.5)" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="medium_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none" enable_animation="true" animation="fade-in-from-bottom"][vc_column_text css_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1563986713426{padding-top: 150px !important;padding-bottom: 150px !important;}"]Exposition Universelle Paris 1900

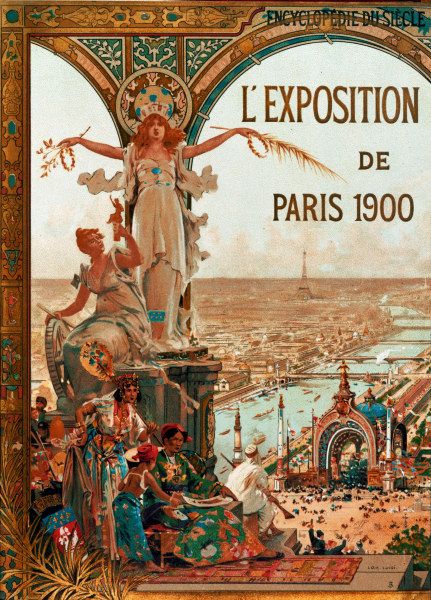

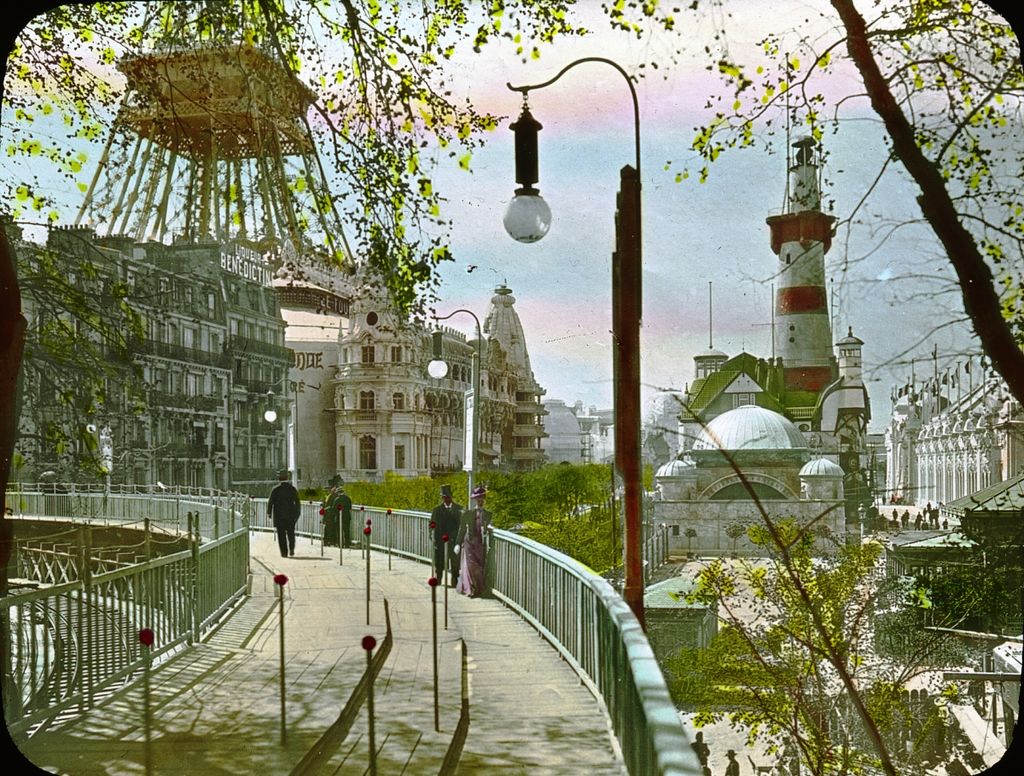

Beginning of Art Nouveau in Paris[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text css=".vc_custom_1563986750278{margin-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;}"]Le Château d'eau, Exposition Universelle, 1900, Paris, France.

Source: Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division

Â[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/2" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]Paris, Dance, and Art Nouveau

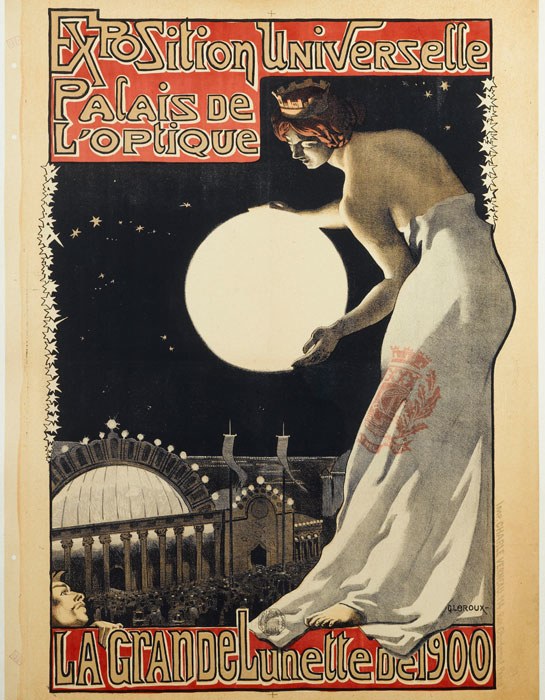

The Exposition Universelle of 1900 was a true and stupendous world’s fair. It was held in Paris to celebrate the achievements of the past century and to help speed up developments in the next. While the 1889 Paris Exposition for which the Eiffel Tower had been erected, was to inaugurate a modern style of technological innovation that demonstrated its possibility of creating cultural monuments with the materials of industrial production, the focus of 1900 Paris Universelle was on culture, especially in the field of art, crafts, and architecture. This fair, which attracted nearly 50 million visitors, displayed many machines, inventions, and architectural feats which have become universal household items such as the diesel engine, talking films, escalators, and the telegraphone (the first magnetic audio recorder), was also devoted to displayed the arts and cultures of foreign lands. As one critic declared that the 1900 Exposition is the Orient’s “grandest and brightest†expansion yet. Not surprisingly, much of the public interest in the Exposition was focused on the seemingly endless varieties of cultures that were available for sampling. From food and drink to cigarettes and postcards, everything made “the Other†accessible in an unprecedented fashion.[cite note="footnote"][4][/cite] One of the places where this exchange of culture took place was at the “Palais de Dance†which was established at the 1900 Paris fair and was devoted to dance from all over the world.

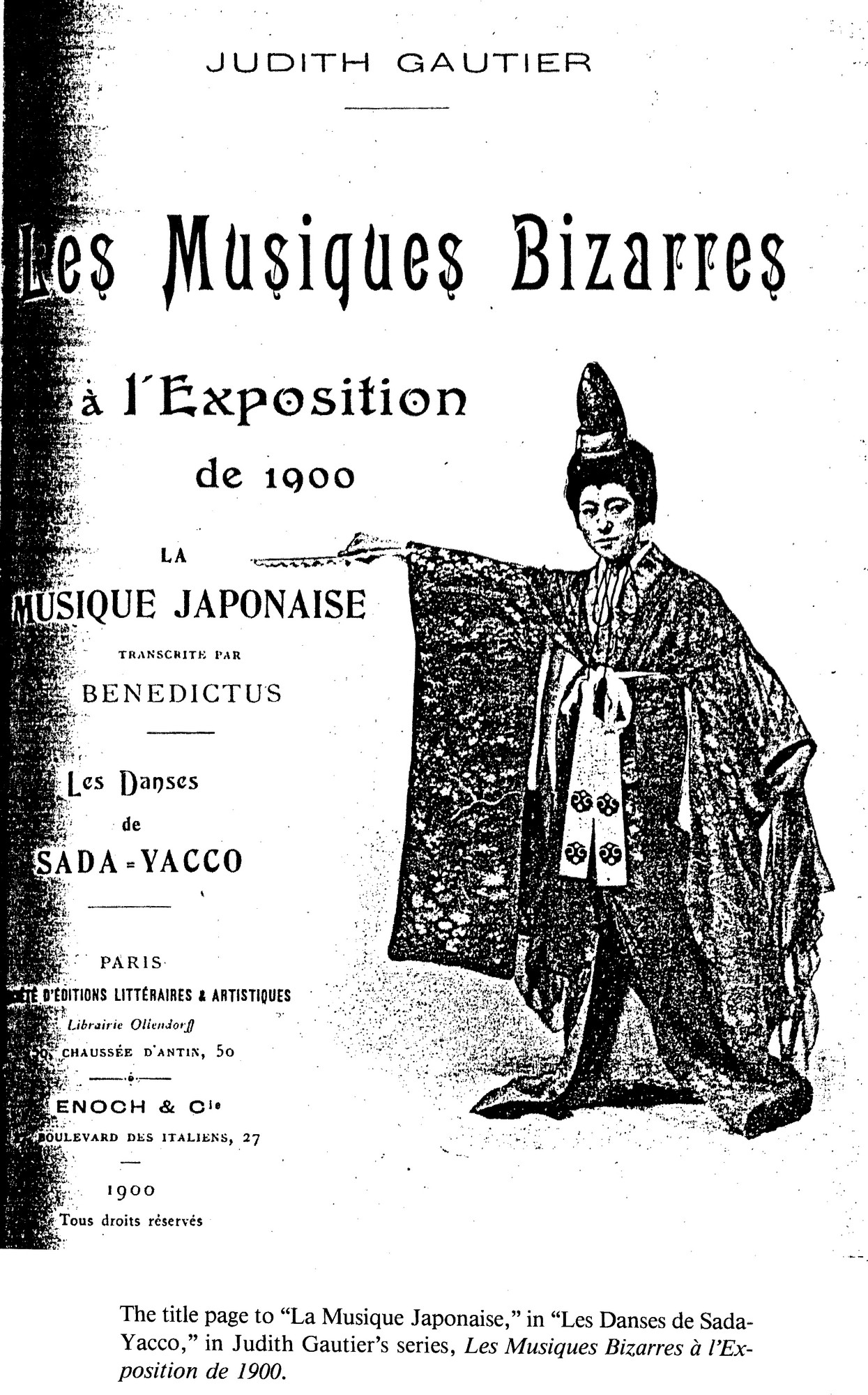

The Exposition Universelle was also a celebration of the Art Nouveau movement where Japanese art played a central role. Since the 1870s, Japanese furniture, paintings, lacquerware, metalwork, and some woodblock prints with Japanese landscapes had become widely known in Europe. Eventually, woodblock prints of no great cultural standing in Japan that were depicting theater actors, famous geisha with their bold graphic design and colors became the rage among European artists ranging from van Gogh to Manet and Klimt. They also were the inspiration for floral patterns in the performances held at the theater of “la Loïe.†Modernity celebrated its global claim through interaction with other cultures.

With its signature dynamic style dominating buildings, art work, posters and performances. The fair also turned the streets of Paris into free art galleries where masterpieces by Toulouse-Lautrec, Steinlein, or Bonnard could be seen, many of them devoted to capture the spirit of Loïe Fuller’s dance.[/vc_column_text][nectar_btn size="large" open_new_tab="true" button_style="see-through-2" hover_text_color_override="#ffffff" icon_family="none" url="https://www.artsy.net/series/art-history-101/artsy-editorial-art-nouveau" text="What is Art Nouveau?"][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/2" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="image_grid" images="2064,1854,2083,2077,1855,1853,2062,2096,2085" display_title_caption="true" layout="2" masonry_style="true" bypass_image_cropping="true" item_spacing="5px" gallery_style="4" load_in_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1569013710049{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" bg_image="1784" bg_position="left top" bg_repeat="no-repeat" bg_color="#303030" scene_position="center" mouse_sensitivity="20" text_color="light" text_align="left" id="movement-goes-global" row_name="Movement Goes Global" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner background_image="2068" enable_bg_scale="true" column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color="rgba(48,48,48,0.5)" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="medium_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none" enable_animation="true" animation="fade-in-from-bottom"][vc_column_text css_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1563986904802{padding-top: 150px !important;padding-bottom: 150px !important;}"]Movement Goes Global[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text css=".vc_custom_1563986912238{margin-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;}"]Chinese shadow theater box with Loïe Fuller.

Source: Ancient Games Collection

Â

Â[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]Sada Yacco at the 1900 Paris Fair

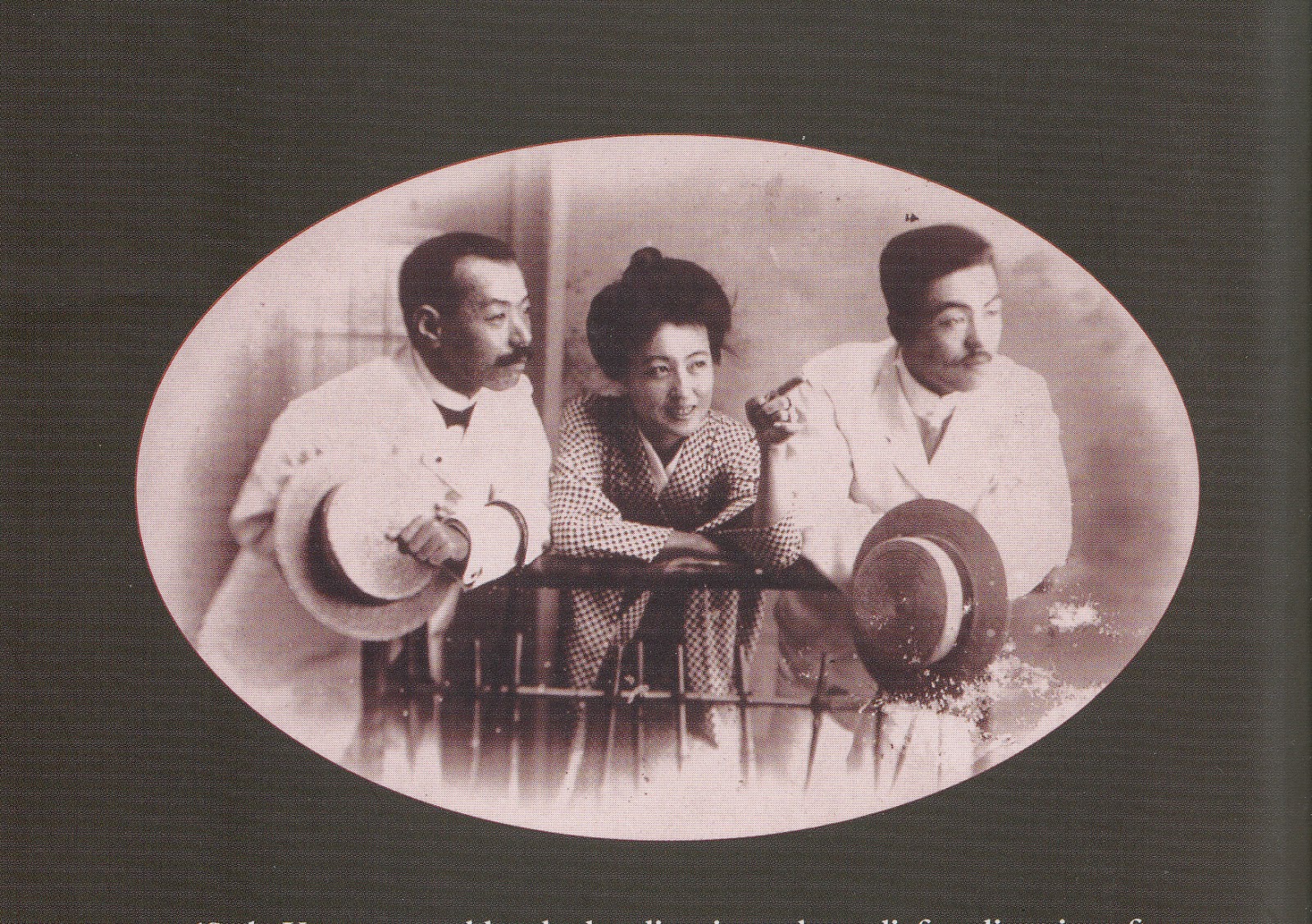

Dancers like Loïe Fuller took inspiration from wherever they could find it, be it the latest discovery of Radium, Art Nouveau, American folk dance, or Asian dance. She was not alone. Asian dance became an inspiration of the imagination for many modern dancers. This imagination dominated the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900. Fuller, who by then had established herself as a leading performer of modernity, had her own Art Nouveau theater in this exhibition, and as a living sign of the emerging globality of modern dance, she invited the Japanese dancer Sada Yacco and her troupe to share the stage with her.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][pop-button-light name="loie" content="Explore La Loïe Theatre" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/popups/la-loie-theatre/"][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="2/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][nectar_image_with_hotspots image="2101" preview="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/69a255_7a573bcc945a4d42802b59c959f9d556_mv2_d_4039_3222_s_4_2.png" color_1="Accent-Color" hotspot_icon="plus_sign" tooltip="hover" tooltip_shadow="none"][nectar_hotspot left="42.0514%" top="58.6606%" position="top"]Location of La Loïe Theatre[/nectar_hotspot][/nectar_image_with_hotspots][vc_column_text css=".vc_custom_1564577677880{margin-top: -20px !important;}"]P. Bineteau, Exposition universelle de 1900 - plan général.

Source: Wikimedia Commons[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" bg_color="#d1d1d1" scene_position="center" layer_one_image="823" layer_two_image="824" text_color="dark" text_align="left" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none" enable_animation="true" animation="fade-in-from-left"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" enable_bg_scale="true" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="2/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="image_grid" images="2069,2072,2094,2084,2074" display_title_caption="true" layout="2" masonry_style="true" bypass_image_cropping="true" item_spacing="5px" gallery_style="4" load_in_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1563987850513{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]Sada Yacco at the La Loïe Theatre

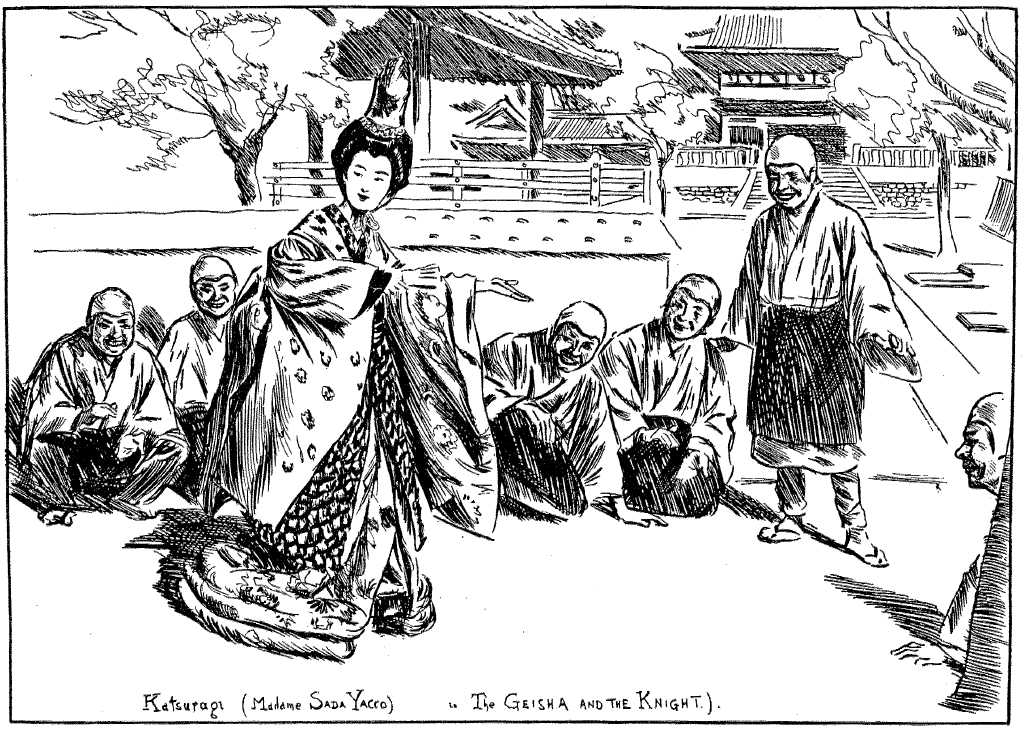

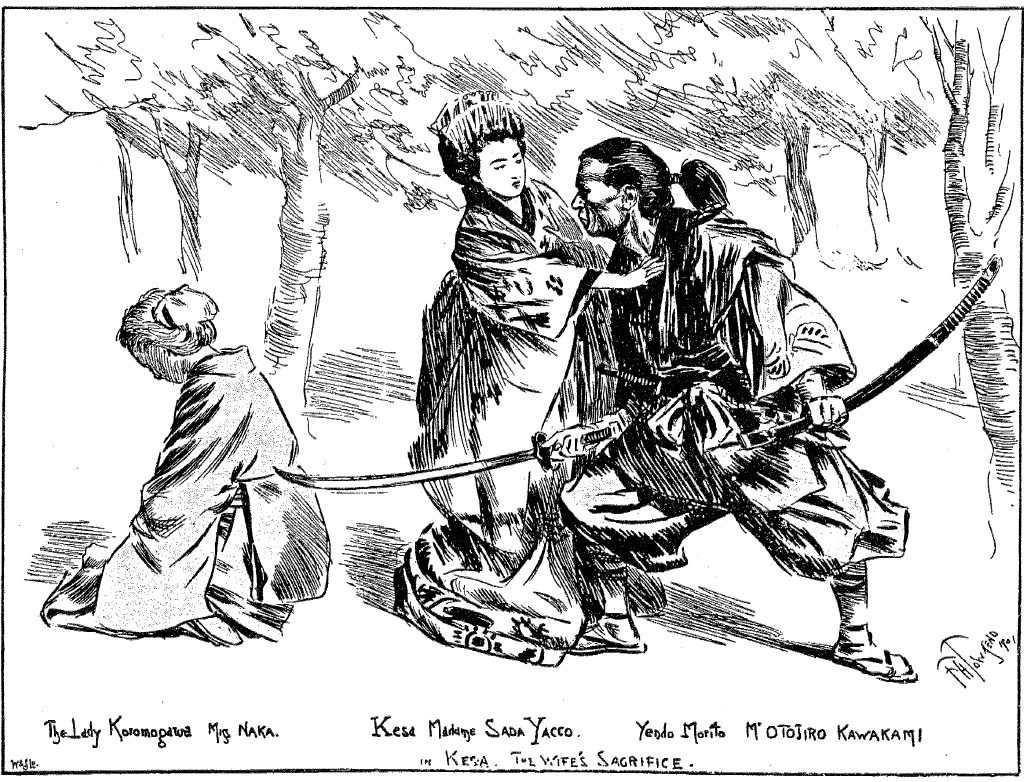

Sada Yacco had come to Paris in 1900 after very successfully touring of the United States a year earlier. She performed with her husband Otojiro Kawakami. Quickly her dance performances became the principal attraction as they roused unparalleled fascination among audiences. At the time, the Japanese Kabuki theater still was largely unknown in the West, and her dance offered a first and deep impression of this aspect of Japanese culture.

Trained as a geisha of the first rank in Japan, she was already a rebel in Japan by performing with her husband in his all-male Kabuki troupe in the new drama style, taking on the women roles previously played by male actors. After coming to the West, she absorbed and adapted some aspects of the Western theater sensibilities and acting styles en vogue at the time. In London, where she went after her New York success, she again won critical and audience appreciation. When she finally came to Paris, her fame was such that “all of Paris rushed to see Yacco, and hundreds were turned away nightly from the Theatre Loïe Fullerâ€[cite note="footnote"][5][/cite] because it was completely sold out. Yacco and Kawakami chose to present exclusively two plays that reinforced a popular Western view of Japan –– Kesa and the Geisha and the Knight. Both works gave Yacco an opportunity to fully display her talents as an actress and a dancer.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" bg_image="1784" bg_position="left top" bg_repeat="no-repeat" bg_color="#303030" scene_position="center" mouse_sensitivity="20" text_color="light" text_align="center" id="fuller-and-yacco" row_name="Loïe Fuller & Sada Yacco" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="medium_depth" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none" enable_animation="true" animation="fade-in-from-bottom"][vc_row_inner equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" column_margin="default" text_align="left" css=".vc_custom_1564578371689{background: rgba(51,13,66,0.54) url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/vintage-paper-background.jpg?id=2966) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;*background-color: rgb(51,13,66) !important;}"][vc_column_inner column_padding="padding-2-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][fancy_box box_style="parallax_hover" icon_family="none" image_url="2102" min_height="400"][/fancy_box][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding="padding-2-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" top_margin="100" bottom_margin="100" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text css_animation="none"]Loïe Fuller and Sada Yacco

Two practitioners of modern dance[/vc_column_text][nectar_btn size="medium" button_style="see-through-2" color_override="#303030" hover_text_color_override="#ffffff" icon_family="none" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/portfolio/loie-fuller-and-sada-yacco/" text="View Photos"][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding="padding-2-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][fancy_box box_style="parallax_hover" icon_family="none" image_url="2103" min_height="400"][/fancy_box][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]Sada Yacco as a Muse

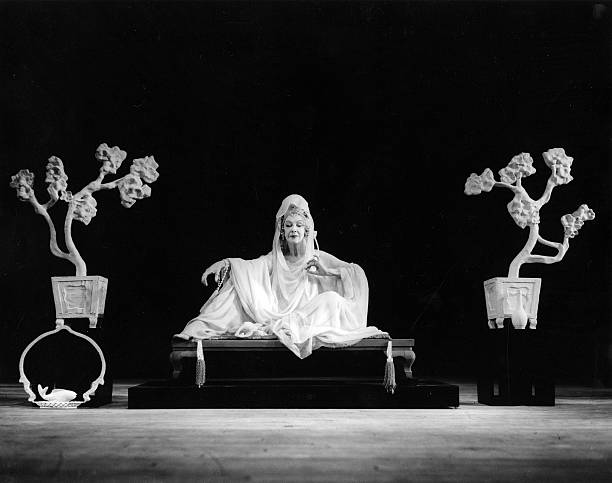

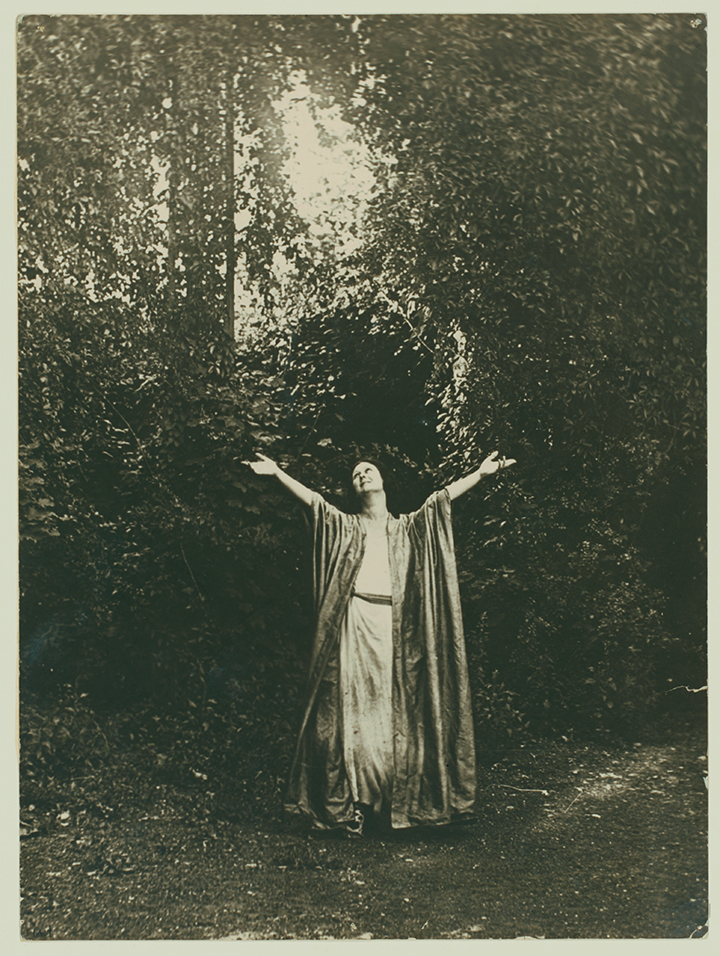

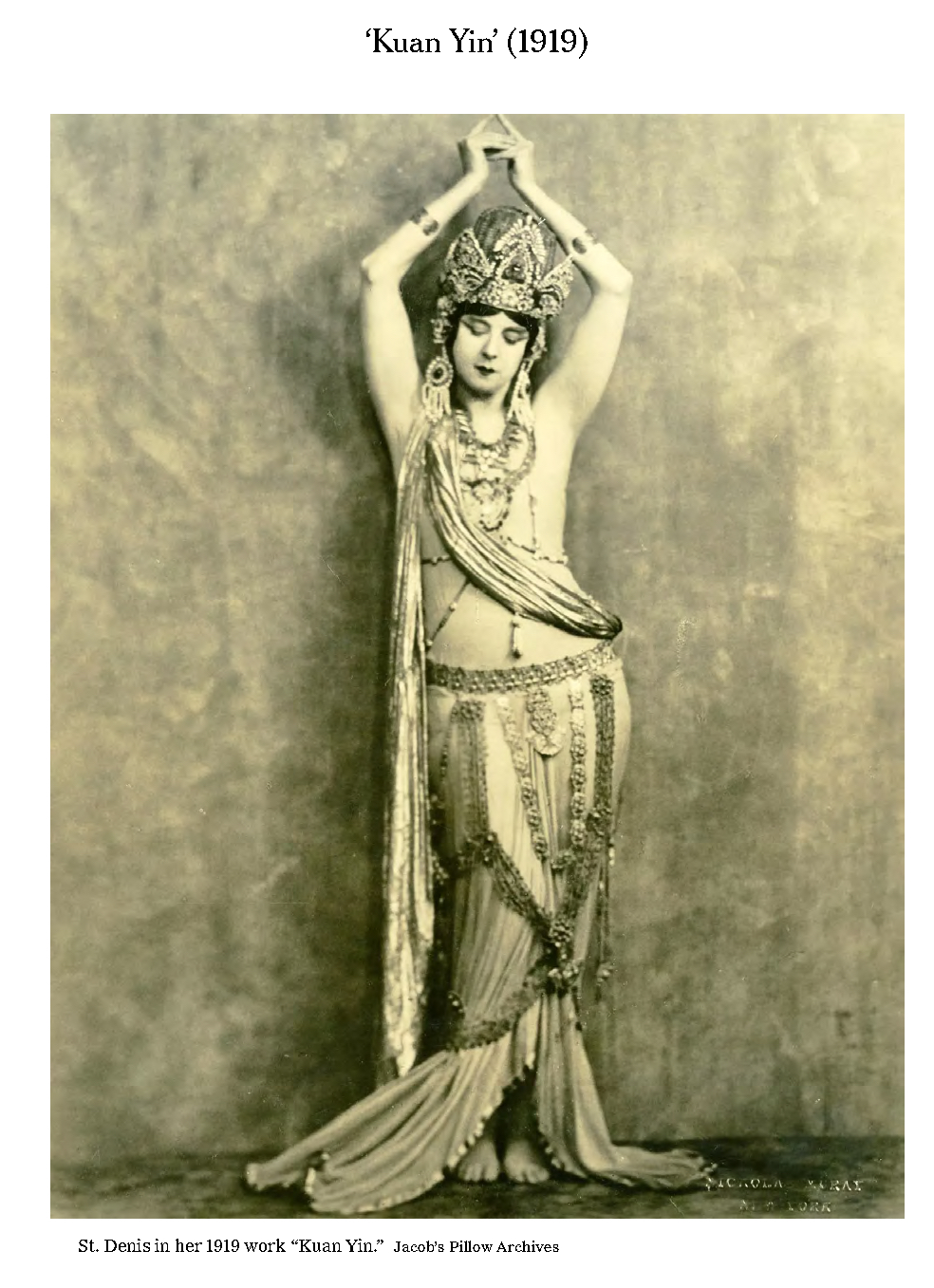

Her impact at the time was immense and long lasting. Her performances of traditional Kabuki and geisha dances, with their symbolic gestures, emphasis on strong visual design, and vividness of execution, were an inspiration for the young artists seeking new paths to define their own style of expressionist dance. Artists such as Isadore Dancan and Ruth St. Denis were beginning to explore previously uncharted territory by defining dance as a vehicle for the communication of personal emotion. Isadora Duncan, much taken with Yacco’s dramatic sensibilities, reconfigured the Japanese dancer’s sense of repose and dynamic ‘stillness’ in her own movements, and these qualities became emblematic of her unique dance expression.

Yacco’s influence on Ruth St. Denis is vividly demonstrated in the latter’s choice of movement style and subject matter as well as her choreography. This is most visibly displayed in her creation of solos such as White Jade which symbolically ‘brought to life’ iconic images of art nouveau through an ornate tapestry of poses. Ruth St, Denis’ fascination with Asian themes for her dances dates from 1900.[cite note="footnote"][6][/cite][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="2/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="image_grid" images="2090,2076,2055,2086,2067,2070,2063" display_title_caption="true" layout="2" masonry_style="true" bypass_image_cropping="true" item_spacing="5px" gallery_style="4" load_in_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1569013476588{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text][footnote note="footnote"]

Footnotes

1. Henri Bergson, L’évolution créatrice, Paris: Alcan, 1907. The Chinese translation came out in 1920 and set off a whole wave of comments. The extensive entry on Bergson in the Xin wenhua cishu 1923, in which this term is explained on p. 52, shows the high standing of Bergson in China at the time.

5. Louis Fournier, Kawakami and Sada Yacco. (Paris: Brentano’s, 1900), p.34.

[/footnote][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

">View SourceReligion: Room 1 Sub-room 1

- Top

- Paris Exposition

- Movement Goes Global

- Fuler & Yacco

[dot-end][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" bg_image="2017" bg_position="left top" bg_repeat="no-repeat" bg_color="#3b414f" scene_position="center" layer_one_image="631" text_color="light" text_align="left" id="image-2-top" row_name="Top of Page" color_overlay="#303030" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="fade-in" shape_type=""][vc_column centered_text="true" column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text css_animation="fadeInDown" css=".vc_custom_1563915531583{margin-bottom: 10% !important;}"]Room No. 2[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text css_animation="fadeInDown"]The Asian Spin at the World’s Fairs

Â[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text el_class="bottom-credit"]Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies, 2008.

Source: McNay Art Musuem[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner equal_height="yes" column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]

Title

The idea for a World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893 came from the Hon. Charles Carroll Bonney (1831-1903), a well-known and successful judge on the Supreme Court of Illinois (Fig. 1). As an active member of the New Jerusalem Church (also known as Swedenborgian), Bonney had a deep conviction about the harmony of religions. He saw the World’s Parliament as “an epoch-making event in the history of human progress, marking the dawn of a new era of brotherhood and peace.”[1]Bonney’s vision reflected the vision of Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition as an exalted celebration of human progress, but it gave it a distinctly religious focus. Bonney hoped that the Parliament would not only bring religious leaders together in an expression of mutual sympathy, but would “unite all religion against all irreligion” (Bonney 1895: 325). This had particular significance for Bonney and other religious leaders who felt both confident and overshadowed by the extraordinary technological prowess that characterized other aspects of the Exposition. To say, as some did, that “Religion is the greatest fact of History,”[2]was not something that one could merely assume. Bonney and others hoped that the Parliament would be a visible demonstration of the importance of religion as a global force amidst the instability of late nineteenth-century modernity.

[1] Charles C. Bonney, “The World’s Parliament of Religions,” The Monist 5 (1895): 322.

[2] John Henry Barrows, The World’s Parliament of Religions. 2 vols. (Chicago: The Parliament Publishing Company, 1893), Vol. 1: vii.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text][vid-box name="videoplayback" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/videoplayback.mp4" thumb="3467"/][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][vid-box name="05994" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/05994.mp4" thumb="3469"/][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][vid-box name="0405" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/0405.mp4" thumb="3471"/][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text][vid-box name="coochee" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/coochee.mp4" thumb="3474"/][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][vid-box name="1821" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/1821.mp4" thumb="3470"/][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][vid-box name="4035" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/4035.mp4" thumb="3479"/][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" bg_color="#d1d1d1" scene_position="center" layer_one_image="823" layer_two_image="824" text_color="dark" text_align="left" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none" enable_animation="true" animation="fade-in-from-left"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="image_grid" images="2052" display_title_caption="true" layout="constrained_fullwidth" masonry_style="true" bypass_image_cropping="true" item_spacing="5px" gallery_style="4" load_in_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1563976396921{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text][vid-box name="LoieFullerPicasso" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/LoieFullerPicasso_sd.mp4" thumb="3478"/]

A clip of Loïe Fuller from the documentary, Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies, 2008. Speaker: Tom Gunning, Film Historian.

[button color="see-through-2" hover_text_color_override="#fff" size="small" url="https://youtu.be/ma_vQvPeSiE" text="See the Full Documentary" color_override="#333333"][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]Motion: The Spirit of the Time

The spin of the Asian dance corresponded to the spirit of the time in Europe which, with the development of steam engine, celebrated speed and motion. The emphasis on dance interacted with an important philosophical shift at the time that again quickly gained a global following. "Movement" was discovered as the true characteristic of modern life, especially that of modern urban life, with its moving vehicles, motion pictures, gas and later electric lights that extended the day into night for work and leisure. It was claimed that these urban dynamics actually reflected the workings underlying the universe.

Henri Bergson (1849 - 1941) theory that the élan vital (= vital energy) was the key characteristic of human life and the driving force of all organisms quickly spread in Europe, Asia, and the Americas.[cite note="footnote"][1][/cite]In 1905, Albert Einstein (1879 - 1955) defined matter in motion as but a form of energy with his famous formula E= mc^2. Years later, the American dancer Loïe Fuller, who also was a member of the French Astronomical Society, tried to organize a discussion between Bergson and Einstein to forge a common ground between biology and physics! "Movement" became the name of honor for collective social engagement, for revolution, and even war. It was celebrated on stage, canvas, in sculpture, in architecture and a magical new invention, the motion picture, was able to record movement and make it visible. No wonder that the Lumière Brothers in France and Thomas Edison in the United States chose to record these fast moving dances to highlight their new invention at market fairs all over the world. Movement was the spirit of modernity. Dance was the ideal carrier of this new spirit.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]Dancing Matter into Motion: Loïe Fuller

The dancer who embodied the new spirit of motion and movement in Paris, the period's "capital of letters", was the American Loïe Fuller, at the time "the most famous dancer in the world.â€[cite note="footnote"][2][/cite] Her experimental spinning dances with stunning light effects and long silk bands were able to create magical illusions and beauty, of matter dissolving into energy. Her spin dancing and her usage of silk sashes show the effects of her encounters with Asian dance.

She rose to fame in Paris in 1892 and the city remained her home until her death in 1928. In the history of modern aesthetics, Fuller's Paris performances during the 1890s such as the Serpentine Dance and the Fire Dance were an inspiration to artists, photographers, and sculptors of artistic trends as different as Art Nouveau and Futurism. Henri Toulouse-Lautrec drew posters for her, Rodin was her friend, and she thought of using radioactive materials discovered by Madame Curie and her husband for light effects. Eventually, her performances were to leave their mark in Asia to which she owed so much.[cite note="footnote"][3][/cite][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="nectarslider_style" images="2095,2071,2088,2060,2079" flexible_slider_height="true" bullet_navigation_style="see_through" onclick="link_image" css=".vc_custom_1569012859567{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" enable_bg_scale="true" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="nectarslider_style" images="2075,2081,2059,2061" flexible_slider_height="true" bullet_navigation_style="see_through" onclick="link_image" css=".vc_custom_1569012868507{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" bg_color="#d1d1d1" scene_position="center" layer_one_image="823" layer_two_image="824" text_color="dark" text_align="left" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none" enable_animation="true" animation="fade-in-from-left"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" enable_bg_scale="true" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/2" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="image_grid" images="1852,2056" display_title_caption="true" layout="2" masonry_style="true" bypass_image_cropping="true" item_spacing="5px" gallery_style="4" load_in_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1563988068290{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/2" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]When West Meets East

While concepts of “movement†as the spirit of modern times quickly spread to Asia especially to the countries engaging in political and social reform like Japan and China, dance movements in the sense of dance forms also migrated to the west from Asian cultures through the world fairs. Dancers like Loïe Fuller are a prime example of the fruitfulness of these cultural encounters. Asian dance became an inspiration for modern dancers, it stimulated their imagination of modernity. Fuller’s famous sash dance with its swinging motions is an example. It might have been inspired by East Asian dancers performing at the world fairs. In the 1895 poster (on the right) we see a Vietnamese-Chinese dancer dancing with colored sashes with movements indicating swinging and turning. Such a silent migration of forms, gestures, and accoutrements is a common and often overlooked feature in cultural exchanges.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="2/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]The Migration of Form

Dance forms migrate but this never is a question of simply copying. As they are seen and appreciated by dancers from other cultures, they act as inspiration to develop something new. The result will look quite different, but a careful study will reveal the traces of this inspiration.

The films that captured the dance movements of the three Japanese dancers (top, 1894) and of Loïe Fuller (bottom, 1900) both emphasize motion and the celebration of it. The motion of the silk sash in both dances give the dance its outer structure. In both dances, moreover, movements tend to be abstract instead of narrative. The Japanese dance resemble the very popular East Asia ribbon dance with silk being thrown into the air by the dancer. While Fuller’s dance steps suggest that they are indebted to tradition, her movement becomes abstract in form as the body of the dancer disappears in the motion of the silk cloth, leaving a moving image entirely formed by the whirling shape of the silk. The floral patterns in Fuller’s silk dance, furthermore, recalled the Japanese lily which was a dominant motif in the Art Nouveau movement. Fuller’s silk sash dance can be considered the emblem of “Art Nouveau style†of dance, and Art Nouveau sculptors, graphic artists, photographers, and porcelain decorators left and endless array of works depicting this dance of hers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text][vid-box name="4031" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/4031.mp4" thumb="3479"/][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][vid-box name="serpentina" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/serpentina.mp4" thumb="3480"/][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" bg_image="1784" bg_position="left top" bg_repeat="no-repeat" bg_color="#303030" scene_position="center" mouse_sensitivity="20" text_color="light" text_align="left" id="exposition-universelle-paris" row_name="Exposition Universelle Paris" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner background_image="2089" enable_bg_scale="true" column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color="rgba(48,48,48,0.5)" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="medium_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none" enable_animation="true" animation="fade-in-from-bottom"][vc_column_text css_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1563986713426{padding-top: 150px !important;padding-bottom: 150px !important;}"]Exposition Universelle Paris 1900

Beginning of Art Nouveau in Paris[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text css=".vc_custom_1563986750278{margin-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;}"]Le Château d'eau, Exposition Universelle, 1900, Paris, France.

Source: Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division

Â[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/2" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]Paris, Dance, and Art Nouveau

The Exposition Universelle of 1900 was a true and stupendous world’s fair. It was held in Paris to celebrate the achievements of the past century and to help speed up developments in the next. While the 1889 Paris Exposition for which the Eiffel Tower had been erected, was to inaugurate a modern style of technological innovation that demonstrated its possibility of creating cultural monuments with the materials of industrial production, the focus of 1900 Paris Universelle was on culture, especially in the field of art, crafts, and architecture. This fair, which attracted nearly 50 million visitors, displayed many machines, inventions, and architectural feats which have become universal household items such as the diesel engine, talking films, escalators, and the telegraphone (the first magnetic audio recorder), was also devoted to displayed the arts and cultures of foreign lands. As one critic declared that the 1900 Exposition is the Orient’s “grandest and brightest†expansion yet. Not surprisingly, much of the public interest in the Exposition was focused on the seemingly endless varieties of cultures that were available for sampling. From food and drink to cigarettes and postcards, everything made “the Other†accessible in an unprecedented fashion.[cite note="footnote"][4][/cite] One of the places where this exchange of culture took place was at the “Palais de Dance†which was established at the 1900 Paris fair and was devoted to dance from all over the world.

The Exposition Universelle was also a celebration of the Art Nouveau movement where Japanese art played a central role. Since the 1870s, Japanese furniture, paintings, lacquerware, metalwork, and some woodblock prints with Japanese landscapes had become widely known in Europe. Eventually, woodblock prints of no great cultural standing in Japan that were depicting theater actors, famous geisha with their bold graphic design and colors became the rage among European artists ranging from van Gogh to Manet and Klimt. They also were the inspiration for floral patterns in the performances held at the theater of “la Loïe.†Modernity celebrated its global claim through interaction with other cultures.

With its signature dynamic style dominating buildings, art work, posters and performances. The fair also turned the streets of Paris into free art galleries where masterpieces by Toulouse-Lautrec, Steinlein, or Bonnard could be seen, many of them devoted to capture the spirit of Loïe Fuller’s dance.[/vc_column_text][nectar_btn size="large" open_new_tab="true" button_style="see-through-2" hover_text_color_override="#ffffff" icon_family="none" url="https://www.artsy.net/series/art-history-101/artsy-editorial-art-nouveau" text="What is Art Nouveau?"][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/2" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_gallery type="image_grid" images="2064,1854,2083,2077,1855,1853,2062,2096,2085" display_title_caption="true" layout="2" masonry_style="true" bypass_image_cropping="true" item_spacing="5px" gallery_style="4" load_in_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1569013710049{padding-top: 2% !important;padding-right: 2% !important;padding-bottom: 2% !important;padding-left: 2% !important;background-image: url(http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ezgif-2-8624f6867063.jpg?id=735) !important;}"][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" bg_image="1784" bg_position="left top" bg_repeat="no-repeat" bg_color="#303030" scene_position="center" mouse_sensitivity="20" text_color="light" text_align="left" id="movement-goes-global" row_name="Movement Goes Global" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner background_image="2068" enable_bg_scale="true" column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color="rgba(48,48,48,0.5)" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="medium_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none" enable_animation="true" animation="fade-in-from-bottom"][vc_column_text css_animation="none" css=".vc_custom_1563986904802{padding-top: 150px !important;padding-bottom: 150px !important;}"]Movement Goes Global[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text css=".vc_custom_1563986912238{margin-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;}"]Chinese shadow theater box with Loïe Fuller.

Source: Ancient Games Collection

Â

Â[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type="full_width_background" full_screen_row_position="middle" equal_height="yes" content_placement="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" id="introduction" row_name="Introduction" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" bg_image_animation="none" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="padding-6-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_row_inner column_margin="default" text_align="left"][vc_column_inner column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="1/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][vc_column_text]Sada Yacco at the 1900 Paris Fair

Dancers like Loïe Fuller took inspiration from wherever they could find it, be it the latest discovery of Radium, Art Nouveau, American folk dance, or Asian dance. She was not alone. Asian dance became an inspiration of the imagination for many modern dancers. This imagination dominated the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900. Fuller, who by then had established herself as a leading performer of modernity, had her own Art Nouveau theater in this exhibition, and as a living sign of the emerging globality of modern dance, she invited the Japanese dancer Sada Yacco and her troupe to share the stage with her.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][pop-button-light name="loie" content="Explore La Loïe Theatre" url="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/popups/la-loie-theatre/"][/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner background_image="1030" column_padding="padding-1-percent" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_shadow="small_depth" column_border_radius="none" column_link_target="_self" width="2/3" tablet_width_inherit="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid" bg_image_animation="none"][nectar_image_with_hotspots image="2101" preview="http://beta.asiaworldsfairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/69a255_7a573bcc945a4d42802b59c959f9d556_mv2_d_4039_3222_s_4_2.png" color_1="Accent-Color" hotspot_icon="plus_sign" tooltip="hover" tooltip_shadow="none"][nectar_hotspot left="42.0514%" top="58.6606%" position="top"]Location of La Loïe Theatre[/nectar_hotspot][/nectar_image_with_hotspots][vc_column_text css=".vc_custom_1564577677880{margin-top: -20px !important;}"]P. Bineteau, Exposition universelle de 1900 - plan général.