The Happenings of the Parliament

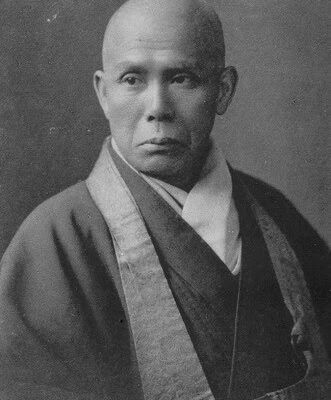

Shaku Sōen

The Law of Cause and Effect as Taught by the Buddha

In this first of two speeches that the Zen master presents, he tackles the question, “Why do things change?” To answer it, he confides in the Buddha’s law of cause and effect. He explains the five concepts that comprise Buddha’s law. He asserts that there is no effect that can arise without several causes having preceded it, and each one of those causes are in and of themselves effects of causes that preceded them. In essence, Sōen teaches the audience that this ad finitum relationship between cause and effect leads to the conclusion that the universe has no real beginning. Everything is part of a constant causal loop that has no discernable start or end. Next, he then extrapolates this continual causal loop onto the second principle that talks about what he calls “the three worlds”: past, present and future. He says that while almost all religions consider the effect that one’s conduct in their present life will have on their future, Buddhism takes this causal inference one step further and says that one’s past life inevitably affects the present one which they are living. Therefore, if one is suffering in their present life, it is because they acted poorly in their past, whereas if they are living happily in the present it is because they conducted themselves well in their past life.

The fourth principle is familiar to those that have studied Buddhism even remotely. It is the idea that both happiness and suffering are born out of our own actions, rather than by an omnipotent deity. Sōen says that Buddhism refers to this as “self-deed and self-gain” and explains the concept quite succinctly when he says, “Heaven and hell are self-made. God did not provide you with a hell, but you yourself.” Finally, he introduces the last principle, which is perhaps the most fundamental of them all. Sōen states that this law is not the cause of an external power, but rather of nature, implying that this is simply how the world works. He does not claim an interventionist god is responsible for happiness or misery, but stresses that humans are the sources of these feelings and conditions, which are products of our past and present actions. Because of this, he emphasizes, “Be kind, be just, be humane, be honest” and people will lead happier lives. The causal law, he asserts, is “the source of moral authority.”

Arbitration Instead of War

In his second address to the Parliament, Sōen is much less cordial. In the very first line, he anticipates the Christian delegates will not take his opinions seriously simply because he is Japanese:

“I am a Buddhist, but please do not be so narrow-minded as to refuse my opinion on account of its expression on the tongue of one who belongs to a different nation, different creed and different civilization.”

He then goes on to discuss a need for a “religion of truth” that will allow for arbitration between opposing nations instead of war. Pointing out that some have claimed the Parliament would be, “Broad, but fruitless”, he calls his fellow delegates to join together in brotherhood in hopes of fostering peace and understanding between peoples of different races and creeds. He expresses a fear that although current international law has done well to promote arbitration, it will eventually not be enough as conflicts become more complex and numerous. Thus, he asserts a need for, “the abolition of war and the establishment of a peace-making society”.

The ending of the speech is surprising given his earlier sentiments of brotherhood. Once again anticipating the Christian delegates’ dismissal, he urges them not to discriminate against him-and the Japanese people as a whole- on the basis of race, civilization, creed or faith. He implores them not to dismiss them just because they are “yellow people”, emphasizing that, “All beings in the universe are in the bosom of truth”. Sōen concludes his remarks with a less agitating statement about how all people are the sisters and brothers of truth, and that we should strive for mutual understanding and respect.

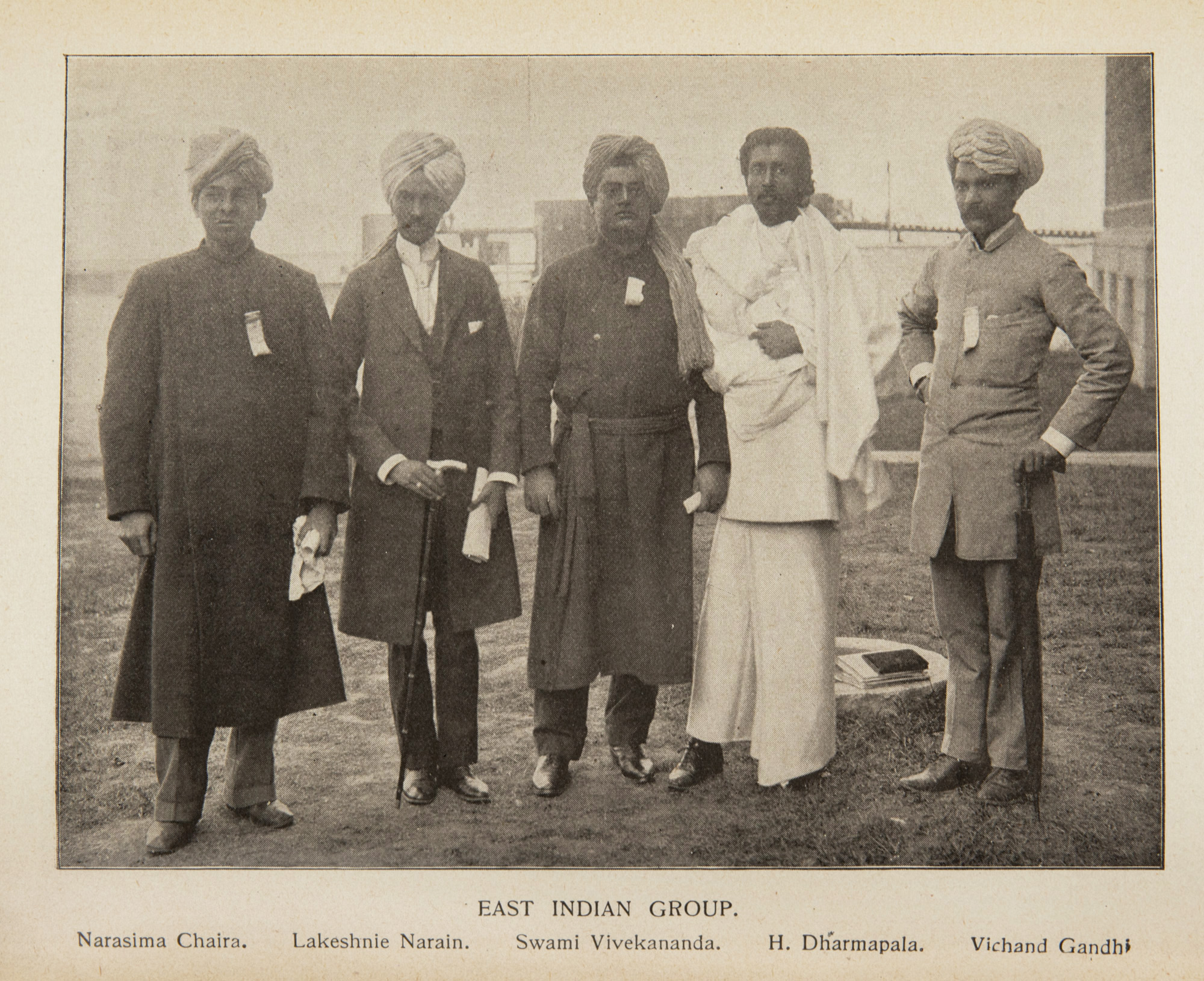

Swami Vivekananda

Hinduism

The Swami devotes his address to answering the question of the origin and makeup of the Hindu faith. As he describes, Hinduism is comprised of “the spiritual flights of Vedantic philosophy, … the agnosticism of Buddhism, … the atheism of the Jains, … and the low ideas of idolatry with the multifarious mythology.” What, then, reconciles these distinct features and allows them to coexist under the name of one religion? That is precisely what the Swami sets out to answer.

He begins by introducing the Vedas, or as he refers to them, the spiritual laws. Similar to Buddhism, the Vedas say that there is no beginning and no end. He extrapolates this idea further, and says that creation has no beginning and no end, for there was and will always be creation and destruction. This cyclical nature, however, does not apply to us as humans because we are not merely our bodies but our souls. For this reason, he declares that our souls were therefore not created, because if they were, they would inevitably have to be destroyed according to the cycle of creation and destruction.

Our souls, he says, are brought about from past lives, and they move from one body to another that is the “fittest instrument” according to the actions of that soul in its past life. These he calls the soul’s tendency, and it helps determine the kind of life that it will lead in the present. This is the explanation for why some people live happy, prosperous lives while others lead miserable ones. It is one of the central doctrines borrowed from Buddhism. The Swami also contends that Hinduism, unlike other religions, does not attempt to answer the question of why certain souls end up in certain bodies. He claims that Hinduism puts forth a simple explanation: “We do not know”.

The swami then goes on to address the concept of sin. Quite boldly considering the majority of his audience is Christian, he asserts that in Hinduism, it is a sin to label someone as a sinner. As he claims, labeling someone a sinner is “a standing libel on human nature”. One could see how Vivekananda’s intention in sharing this of the many important aspects of Hinduism could have been as a form of criticism against Christianity, most likely influenced by his witnessing of Christian missionary efforts in India. The same could be said of his comments about how love is taught through Hinduism. Krishna, whom the Hindus believe to be God incarnate on Earth, taught that while it is acceptable to love God in the hope of receiving reward in a next life, all the better to love God for the sake of loving Him. Again, it seems as though he is trying to make a subtle comparison between the Hindu doctrine and the Christian gospel in an attempt to demonstrate Hinduism’s relative altruism.

Man being comprised of a soul that is only bound to the human form through matter is a vital aspect of the Hindu teachings. The ultimate goal of Hinduism is for man to break from the “terrible law of causation” that is the soul moving from one body to the next. The swami says that only God can relieve one from this eternal cycle, to allow one to bask in the life beyond “ordinary sensual existence”. Therefore, Hinduism does not believe in convincing people to follow a specific doctrine. Rather, it looks to convince by the realization of the soul, and therefore of God. In order to realize God, the Hindu strives for perfection and “to become divine”. This, the swami proclaims, is what constitutes the religious beliefs of Hinduism.

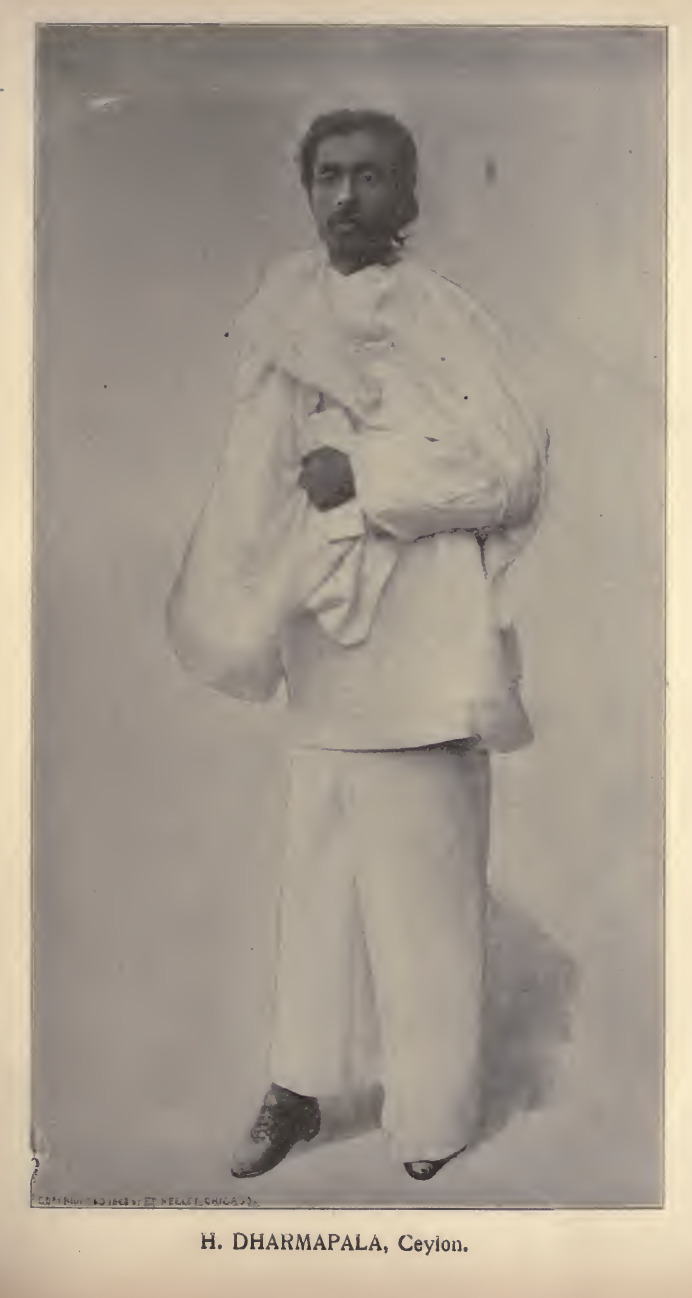

Anagarika Dharmapala

Criticism and Discussion of Missionary Methods

Dharmapala gave a short speech as part of a small series of addresses by several delegates about Christian missionary methods. His remarks were straightforward and arguably curt. He declares that missionary methods over the last three centuries have been largely unsuccessful in the East, and he credits that to the missionaries themselves that have been sent. He says that on a whole, the missionaries sent to Asian countries have been “intolerant” and “selfish” and that as a result of this, intelligent natives are reluctant to interact with them. Only low types of people, he argues, have become their converts. In addition, he brings up another equally important point that he does not elaborate much on. When comparing the work of Buddhist and Christian missionaries, he says that the Buddhists were successful in spreading their religion all over Asia, and in making people “mild” in temper as a result. Contrastingly, he says that the work of western civilization, “is undoing their work.” Finally, he says to this younger generation of Christians in attendance that the only way Christianity can become widespread in Asia is if they follow the principles of “Christ’s love and meekness.”

Points of Resemblance and Difference Between Buddhism and Christianity

As the name implies, Dharmapala’s second speech is a comparison of Buddhism and Christianity. He begins the discussion by comparing the Buddhist and Christian approaches to inequality among men, stating that Buddhism explains this phenomenon through one’s actions in his or her past and present life, thereby eliminating the need for “interference of a personal God”. In contrast, he says that Christianity deals with these injustices through promise of rewards in the future, ostensibly speaking about the prospect of ascension into heaven. His real emphasis is on Buddhism’s doctrine of freedom from desire and selfishness which keeps us tethered to unhappiness and thus leads to a worse life.

He then moves on and provides the audience with a series of Buddhist teachings that he says Christianity has claimed for itself. Then, he provides several more Buddhist teachings as a comparison point between the two religions, showing that many of them preach similar doctrine. Finally, he concludes with two quotations from prolific religious scholars. First, he quotes Max Müller, one of the founders in the western academic discipline of the study of Indian religions. Müller’s words reflect on Buddhism’s prominent position in the historical timeline of development. He remarks that Buddhism is what allowed India to “step forth out from its isolated position and become an actor in the historical drama of the world”. Finally, Dharmapala quotes R.C. Dutt, a well-known Indian civil servant and historian. The passage he quotes from Dutt speaks to Buddhism’s interaction with the Greeks prior to the Christian era, implying that the Buddhist philosophy most definitely could have influenced early Christian thought.

The World’s Debt to Buddha

Dharmapala frames his discussion on Buddhism within the context of ancient India’s religious scene twenty-five centuries ago when, as he puts it, “the air was full of a coming spiritual struggle”. Who was able to make sense of the world and describe a way to absolve people from suffering: the great Buddha. He makes it a point to say that Western scholars of Eastern religions were still unsure of the origins of Buddhism well into the beginning of the nineteenth century. It was not until 1844 when the first comprehensive account of Buddhism was compiled by a scholar named Eugene Burnouf who initiated the discourse throughout European and Western circles.

Dharmapala claims that Buddhism arose out of the culmination of all that was good, leaving all that was bad “to be discarded”, leading to the establishment of what he calls a “synthetic religion”. This religion did away with monotheism and selfish priests, and taught people about the holiness of life on earth and about how to lead a simple, practical, pure life.

The Buddhist missionary then set out to describe to the audience the foundational teachings of the Buddha through his first message to five disciples. First and foremost, he describes the tenant of suffering. Buddha’s Noble Truth of the origin of suffering is quite simple: Life is suffering. As Dharmapala quotes Buddha: “Birth is attended with pain, old age is painful, disease is painful, death is painful, association with the unpleasant is painful, separation from the pleasant is painful… the coming into existence is painful”. Thus marks one of the central tenants of Buddhism. To remedy suffering, Buddha says that one must rid themself of all passions and desires, thus leaving no room for suffering to take root in life. One can accomplish this by following the Eight Fold Path, but Dharmapala does not venture to describe the Path in detail. He concludes that the essence of this first speech by the Buddha is the obliteration of evil, the consummation of the good and pure, and the purification of the mind.

Next, he engages with Western scholar’s interpretation of Buddhism. He claims that no systemic structure has been put forward to studying Buddhism, and that this has led to vastly different classifications of the religion such as materialistic, positivistic, agnostic, monotheistic, panistic, and monistic. At its core, Dharmapala says, Buddhism is a doctrine focused on the “self-purification of man” so that spiritual progress can be realized. Its end goal is to give man a way for truth to enter the mind. Truth is the ultimate protection from passion, prejudice and ignorance, as well as the ultimate spark of universal love and sympathy.