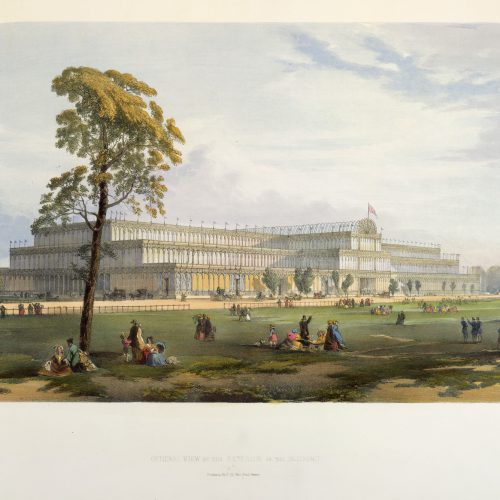

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, or the “Crystal Palace Exhibition,” London, 1851

One of the earliest major international exhibitions was the “Crystal Palace” in London, named after the enormous glass and iron structure that housed it in Hyde Park as a celebration of British industrial might. It promoted a goal of peaceful intercourse among nations and provided a stage with which to drive home to its huge audiences ideas of social and industrial progress. The exhibits made it increasingly clear which nations were progressive, and which were not.